Years ago, I wrote a bestselling book called 9 Habits of Highly Profitable Writing. I’m assaying a second edition now, and that process includes posting each of the habits here for you, for free.

Habit Two: Dress Up

Habit Two: Dress Up

Yes, freelance writing often means you get to telecommute.

Yes, that means my work day starts and ends with me in my jammies and a three-day stubble on my face. Yes, people who come to my door are lucky I’m wearing pants. Yes, this is one of the best parts of my job.

And yet….

You still have to maintain a professional appearance. The “face” you put forward to potential clients will determine whether or not they offer you a chance to impress them with your writing skills.

There’s a story…

Husband: Honey, would you still love me if I was ugly?

Wife: If you turned ugly tomorrow – got burned in a fire, or cursed by a witch or something – of course I’d still love you. It’s the parts on the inside that I fell in love with.

Husband: Awww. Thanks, honey, that’s just what I needed to hear.

Wife: But if you were born ugly, I wouldn’t have ever asked you out in the first place.

That’s doubly, maybe triply true in the world of finding clients. If you don’t show up at your best, then potential clients will never go on that first date than shows the substance behind your style. This doesn’t just apply to how you personally look.

8 Keys to Looking Good For Potential Clients

- Having a professional website. Does yours look current and professional, or like you hand-coded it using a Dummies book in 1998? Does it demonstrate that you can write coherently, and edit what you write? Does it include current contact information, and a recent resume?

- Maintaining a social media presence. Do you have a compelling profile on at least two social media platforms? Does your content there compel comments, likes, shares and retweets? Do you have a following that you can use to promote clients who hire you? Do your comments demonstrate professionalism and a positive attitude?

- Using images effectively. Are all the images on your website of high quality? Do they show appropriate subject matter? Do your profiles include a photo of you looking good while doing what you do? Do you provide proper accreditation for images you didn’t make yourself?

- Communicating professionally. Do your emails to potential clients observe proper grammar and get your point across as effectively as possible? Do you avoid foul language in your public posts, and in your messages to clients? Do you respond rapidly to questions, and give advance warning if something happens to put you off schedule? Do you follow basic professional protocols in your communication on the phone, in person and via electronic media?

- Maintaining an impressive portfolio. Do you provide compelling and recent work samples related to the jobs you’re seeking? Is there a testimonials page on your website? Do you solicit testimonials from your favorite clients once or twice every year?

- Grooming yourself. Do you see to basic hygiene before meeting somebody in person or via video chats? Can you put on a suit or good dress for important client meetings and initial interviews?

- Have an elevator pitch. Can you communicate what you write, and why you’re great at it, in a 2-3 sentence statement taking less than a minute to deliver? Can you deliver it without stuttering or otherwise sounding unprofessional?

- Getting those letters. They don’t have to be Ph.D. or MFA, but any kind of awards, testimonials, speaking credentials, or similar badges of authority go a long way towards making you look like a serious professional doing serious work.

If you have to answer “no” to some or even most of these questions, don’t panic. You’ve simply identified a few of the habits you need to build over the next several weeks.

Avoiding Dealbreakers

Here’s another story.

In 2014, I would take my toddler son (now 8 years old) to buy groceries. He liked identifying and counting food. I liked getting the job done and spending time with him. It was a win-win father-son outing of lovely proportions.

One day in line, a young woman in front of us offered her nannying services while we were both waiting at the register. A total stranger hit me up for a job, just like I tell all my writing coaching clients to do. She did a lot of things right.

- She observed the first rule of freelance job hunting: tell everybody you meet what you do, and ask them to pay you for doing it.

- She opened the conversation by demonstrating her knowledge of her field. In this case, she engaged me about parenting and her experience with children.

- She asked me for work in a straightforward, almost abrupt, manner.

- She told me about her past experience, and offered to provide references.

- Her entire communication was professional, yet approachable and friendly.

It was an excellent pitch, but I never called her. Despite having five things in her “pro” column, she had two in the “neg” that absolutely nixed any possibility of my hiring her.

Reason #1: She was dressed in a ratty sweatshirt and very (very) tight camo pants. Sure, it was Sunday morning at the grocery store, and she even apologized for the outfit. But if you’re in the game of asking for work every time you leave the house, you should dress for work every time you leave the house. It made me wonder what other details she was in the habit of forgetting.

Reason #2: She smelled like cigarette smoke. I don’t consider this the sin a lot of people seem to think it is these days, but it is a deal-breaker for anybody who wants to spend time with my kid. My attitude on this is pretty common up here in the granola-chewing, tree-hugging, holier-than-thou Pacific Northwest. She’d neglected to do basic market research in her chosen field.

Two small details of her appearance outweighed multiple excellent points in her favor. Remember: the people who make decisions about hiring freelancers are besieged by people asking for work. They’re not looking for reasons to say yes. They’re looking for reasons to say no.

Don’t give them easy reasons. You should never miss out on a client just because you didn’t feel like getting permission to use a photo, or put on your grownup pants on your way to get some milk. On the job, on the web, and in the world…dress up of you want to make it as a freelancer.

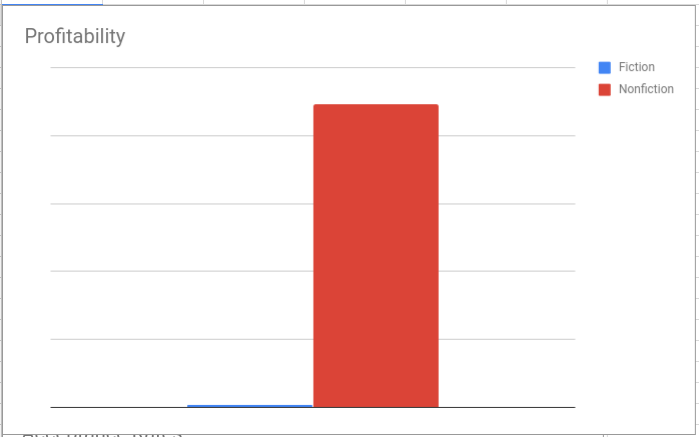

Habit One: Write Nonfiction

Habit One: Write Nonfiction

I want to tell you a story about a man who, four years ago, dreamed of becoming an author. I knew what I wanted to do, but I wasn’t sure how to go about it. I’m a semi-retired (semi because I can’t make myself stop working) businessman, educator, and consultant.

I want to tell you a story about a man who, four years ago, dreamed of becoming an author. I knew what I wanted to do, but I wasn’t sure how to go about it. I’m a semi-retired (semi because I can’t make myself stop working) businessman, educator, and consultant.

So I’m hanging out this morning with several professionals in the publishing and writing industries, after almost two weeks of doing the same. We’re all raging against the obvious mistakes people make before sending a query letter to an agent or editor.

So I’m hanging out this morning with several professionals in the publishing and writing industries, after almost two weeks of doing the same. We’re all raging against the obvious mistakes people make before sending a query letter to an agent or editor.